By Dennis Hartley

(Originally posted on Digby’s Hullabaloo on October 23, 2021)

I confess that I initially felt out of my depth tackling Jason Baker’s documentary Smoke & Mirrors: The Story of Tom Savini. I knew Savini was an actor, primarily from George Romero’s Knightriders (one of my favorite cult movies) and two Robert Rodriguez films: From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) and Planet Terror (2007). What I did not know (embarrassingly) was that despite 77 acting credits, he is more revered by horror fans and industry peers for his makeup artistry and (disturbingly) realistic special effects wizardry.

Perhaps I can be forgiven; looking up his special effects/makeup credits, it turns out I have only seen 3 out of dozens. I am not averse to the horror genre per se, it’s just that I’m not a fan of slasher/gore films; I tend to avoid them altogether.

But since (to paraphrase Marlon Brando in The Godfather) “it doesn’t make any difference to me what a man does for a living” (with the proviso no one is harmed in the process), I plowed forward with an open mind and an impending deadline and found Baker’s film to be a surprisingly warm, engaging portrait of a genuinely interesting artist.

The big surprise is how soft-spoken Baker’s subject is; especially when his resume reads more like a slaughterhouse tour than a fun night at the movies: Dawn of the Dead, Friday the 13th, Maniac, Creepshow, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, Trauma, Machete, et.al.

Savini grew up in a working-class Pittsburgh neighborhood and developed a talent for performing magic tricks at an early age. He also became obsessed with the 1957 Lon Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces. He recalls experimenting with various household products to create his own horror makeup, to freak out his family and friends. Obviously, this kid was destined for a life on the stage …or in front of a movie camera.

The most fascinating elements of this predestination were Savini’s experiences in Vietnam, where he served as a combat photographer. Obviously, if your job assignment literally involves focusing on gruesome images day in and day out, it’s going to do a number on your head. Savini describes how he internally compartmentalized the real-life horror of what he saw as “special effects” (which he’d later draw upon for his film work).

Savini also recounts his collaborations with director George Romero, who gave him his first movie gig in his 1976 indie Martin (which was filmed in Pittsburgh). Savini not only acted in the film but created its prosthetic effects. Savini continued to perfect his craftsmanship in higher-budgeted Romero films like Dawn of the Dead and Creepshow.

Some of Savini’s friends and colleagues (Robert Rodriguez, George A. Romero, Alice Cooper, Sid Haig, Corey Feldman) also appear in the film; their consensus is that Savini is a nice guy…even if he makes his living giving us nightmares. In fact, there’s an overdose of people telling us how nice he is (puff piece territory). But he seems like a nice guy. Just attribute all that murder and gory mayhem to …smoke and mirrors.

“Smoke & Mirrors: The Story of Tom Savini” is streaming on various digital platforms.

In an interview published by The Hollywood Reporter in April of 2020, David Lynch made these observations regarding Denis Villenueve’s (then) upcoming remake of Dune:

(Interviewer) This week they released a few photos from the new big-screen adaptation of Dune by Denis Villeneuve. Have you seen them?

I have zero interest in Dune.

Why’s that?

Because it was a heartache for me. It was a failure, and I didn’t have final cut. I’ve told this story a billion times. It’s not the film I wanted to make. I like certain parts of it very much — but it was a total failure for me.

You would never see someone else’s adaptation of Dune?

I said I’ve got zero interest.

If you had your choice, what would you rather make: a feature film or a TV series?

A TV series. Right now. Feature films in my book are in big trouble, except for the big blockbusters. The art house films, they don’t stand a chance. They might go to a theater for a week and if it’s a Cineplex they go to the smallest theater in the setup, and then they go to Blu-ray or On Demand. The big-screen experience right now is gone. Gone, but not forgotten.

Keep in mind, that interview was conducted during the initial lock-down phase of the pandemic. I don’t know about you, but I am still not “ready” to go back to movie theaters. As I wrote in an October 2020 piece about COVID’s effect on theaters:

…that is my personal greatest fear about returning to movie theaters: my innate distrust of fellow patrons. […] I can trust myself to adhere to a common-sense approach, but it’s been my observation throughout this COVID-19 crisis that everybody isn’t on the same page regarding taking the health and safety of fellow humans into consideration.

I’ve noticed a trend as of late where Hollywood studio marketing departments are insisting that you must see their latest blockbuster on the big screen, otherwise you’re just a fraidy cat, cowering in front of your pathetic little 40” flat-screen. Believe me, as a lifelong movie lover I am pulling for the exhibition arm of the industry and want to see them thrive once again, but to my knowledge, no amount of wishful thinking ever defeated a killer virus. As much as I am dying to see the new Bond movie on a big-ass screen, I’ve decided to hold off a while because for me, this is no time to die.

I suppose this long-winded prelude is my way of giving a disclaimer that the following review of Denis Villenueve’s long-anticipated adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune does not necessarily reflect the opinions of staff or management of Digby’s Hullabaloo, but those of a fraidy cat, cowering in front of his pathetic little 40” flat-screen.

To put your mind at ease, I’m not going to bore you with a laundry list of how the film does or doesn’t adhere to the author’s original vision in the source novel; mainly since it’s been 40-something years since I read it, and all I can remember is that it felt like homework. It just didn’t grab me like the universe-building works of Asimov, Zelazny, Niven, and similar sci-fi scribes my stoner friends and I were all into at the time.

Obviously, David Lynch is not a fan of his own 1984 adaptation; the first time I saw it 37 years ago I wasn’t either …but in the fullness of time, it has grown on me (as Lynch’s films tend to do). Yes, it has certain cheesy elements that even time cannot heal, but how can you possibly top Kenneth McMillan’s hammy performance as an evil, floating bag of pus, Brad Dourif’s bushy eyebrows…or Sting’s magnificently oiled torso?

It is evident off the bat that Villenueve’s adaptation (co-written by Jon Spaihts and Eric Roth) is more formalized than Lynch’s; he doesn’t leave his cast as much room to ham it up and distract from the business at hand; but rather uses them like chess pieces.

On the plus side, this makes the plot easier to follow. On the downside, Villenueve runs into the same challenge Lynch faced: there are simply too many characters in Herbert’s novel and not enough time within the constraints of a feature film to give anyone an adequate enough backstory to make you care what happens to them.

The cast is led by Timothée Chalamet as Paul Atreides, rising son of “good” Duke Atreides (Oscar Isaac) and Lady Atreides (Rebecca Ferguson). By decree of the Emperor (of Space? Still unclear to me after a forgotten read and two films), the House of Atreides has been given stewardship of precious “spice” mining operations on the planet Arrakis.

This does not set well with the former dominant House on Arrakis, led by “bad” Duke Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård, who appears to be channeling Lawrence Tierney in Tough Guys Don’t Dance). Duke Atreides’ new gig is further complicated by an insurgency of native “Fremen” (led by Javier Bardem, sans cattle prod) and ginormous worms.

I gave up comparing worm size in grade school, but Villenueve’s worms are more awesome than Lynch’s (there have been significant advancements in digital effects since 1984). Sadly, that’s the best thing I can say about Dune 2021 (or as I’ve nicknamed it, “Spice World 2”). It boasts impressive special effects and world-building, but otherwise, the film is a dramatically flat, somber affair with an abrupt “That’s it?!” denouement. I know sequels are in the works …but would it have killed them to give us a cliffhanger?

“Dune” is currently in theaters and streaming on HBO Max

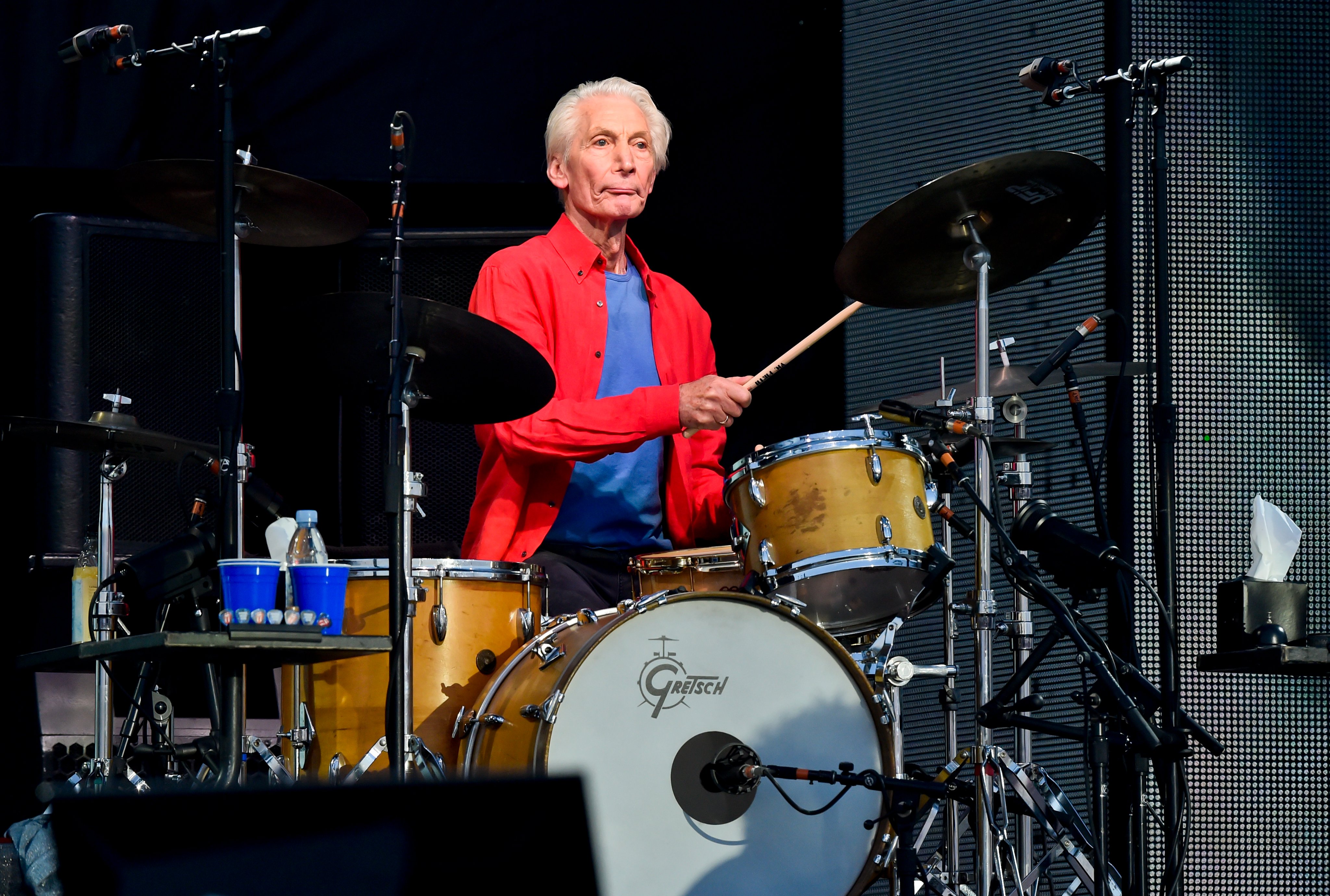

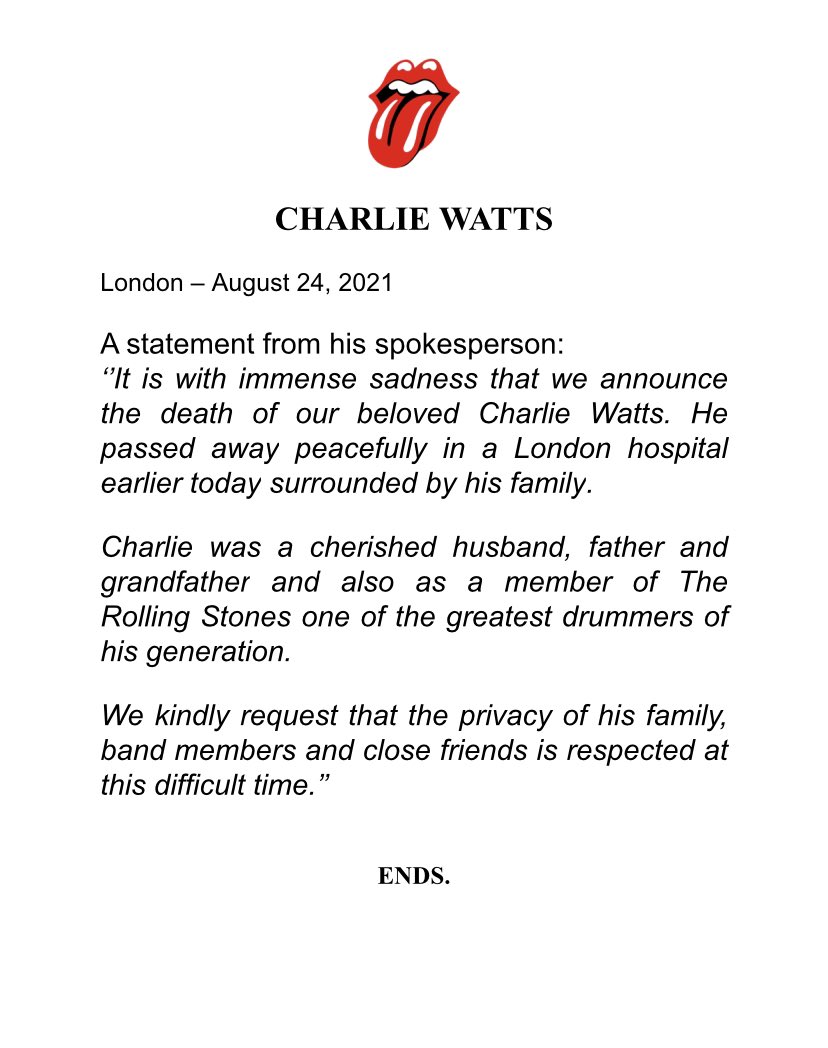

Stalwart to the end, Charlie Watts was the “rock” in rock ‘n’ roll. Solid, reliable, resolute. He sat Sphinx-like behind his kit for over 50 years, laying down a steady beat while remaining seemingly impassive to all the madness and mayhem that came with the job of being a Rolling Stone. He was cool as a cucumber, as impeccably tailored and enigmatic as Reynolds Woodcock. “Reynolds Who?”

Stalwart to the end, Charlie Watts was the “rock” in rock ‘n’ roll. Solid, reliable, resolute. He sat Sphinx-like behind his kit for over 50 years, laying down a steady beat while remaining seemingly impassive to all the madness and mayhem that came with the job of being a Rolling Stone. He was cool as a cucumber, as impeccably tailored and enigmatic as Reynolds Woodcock. “Reynolds Who?”