By Dennis Hartley

(Originally posted on Digby’s Hullabaloo on November 19, 2016)

Well it’s 1969 OK, all across the USA

It’s another year for me and you

Another year with nuthin’ to do,

Last year I was 21, I didn’t have a lot of fun

And now I’m gonna be 22

I say oh my, and a boo-hoo

-from “1969” by The Stooges

They sure don’t write ‘em like that anymore. The composer is one Mr. James Osterberg, perhaps best known by his show biz nom de plume, Iggy Pop. Did you know that this economical lyric style was inspired by Buffalo Bob…who used to encourage Howdy Doody’s followers to limit fan letters and postcards to “25 words or less”? That’s one of the revelations in Gimme Danger, Jim Jarmusch’s cinematic fan letter to one of his idols.

Jarmusch dutifully traces the history of Iggy and the Stooges, from Iggy’s initial foray as a drummer, to the Stooges’ 1967 debut (then billing themselves as “The Psychedelic Stooges”), to their signing with Elektra Records the following year (which yielded two seminal proto-punk albums before the label unceremoniously dropped them in 1971) to the association with David Bowie that gave birth to 1973’s Raw Power, up to the present.

While LP sales were less than stellar (and forget about radio exposure, outside of free-form and underground FM formats), the band’s legend was largely built on their gigs. From day one, Iggy was a live wire on stage; unpredictable, dangerous, possessed. Whether smearing peanut butter (or blood) on his chest while growling out songs, undulating his weirdly flexible body into gymnastic contortions, or impulsively flinging himself into the crowd (he invented the “stage dive”), Iggy Pop was anything but boring.

Keep in mind, this was a decade before Sid Vicious was to engage in similar stage antics. The peace ‘n’ love ethos was still lingering in the air when the Stooges stormed onstage, undoubtedly scaring the shit out of a lot of hippies. However, once they hitched their wagon to fellow Detroit music rebels/agitprop pioneers the MC5 (their manifesto: “Loud rock ‘n’ roll, dope, and fucking in the streets!”) they began to build a solid fan base, which became rabid. Unfortunately, film footage from this period is scant; but Jarmusch manages to dig up enough clips to give us a rough idea of what the vibe was at the time.

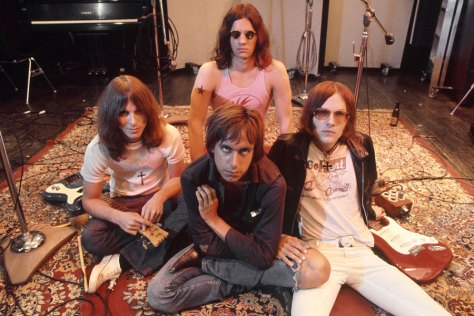

Jarmusch is a bit nebulous regarding the breakups, reunions, and shuffling of personnel that ensued during the band’s heyday (1967-1974), but that may not be so much his conscious choice as it is acquiescing to (present day) Iggy’s selective recollections (Iggy does admit drugs were a factor). While Jarmusch also interviews original Stooges Ron Asheton (guitar), and his brother Scott Asheton (drums), their footage is sparse (sadly, both have since passed away). Bassist Dave Alexander, who died in 1975, is relegated to archival interviews. Guitarist James Williamson (who played on Raw Power) and alt-rock Renaissance man Mike Watt (the latter-day Stooges bassist) contribute anecdotes as well.

Many might assume, judging purely by the simple riffs, minimal lyrics and primal stage persona that there wouldn’t be much going on upstairs with the Ig…but that would be a highly inaccurate assumption. To the contrary, Iggy is much smarter than you think he is; a surprisingly erudite raconteur who is highly self-aware and actually quite thoughtful when it comes to his art. It might surprise you to learn that one of his earliest creative influences (aside from space-jazz maestro Sun Ra and, erm, Soupy Sales) was American avant-garde composer Harry Partch, who utilized instruments made out of found objects.

A few nitpicks aside, this is the most comprehensive retrospective to date regarding this truly influential band; it was enough to make this long-time fan happy, and to perhaps enlighten casual fans, or the curious. As for the rest of you, I say: Oh my, and a boo hoo!

Interestingly, Iggy pops up in another new documentary. In fact, there is much cross-pollination between Gimme Danger and Danny Says (on PPV), Brendan Toller’s uneven yet quaffable portrait of NYC scenester/music publicist/DJ/fanzine editor Danny Fields.

Fields was the talent scout/A&R guy/whatever (his job title is never made 100% clear…more on that in a moment) who “discovered” The Stooges while on assignment from Elektra Records to scope out the Detroit music scene in 1968. While the record company was primarily interested in the MC5, Fields convinced the suits to tack the Stooges on as a “two-fer” signing deal: $20,000 for the MC5 + $5,000 for the Stooges (!)

That’s jumping a bit ahead in Fields’ involvement with the music biz, which appears (according to Toller’s film) to have been attributable to a series of happy accidents, which begins with him falling into a managing editor position with the teenybopper fanzine Datebook in 1966. Within months of landing the gig, Fields found himself at the center of the infamous John Lennon “bigger than Jesus” controversy, stemming from a highlighted quote in a Datebook interview (his editorial decision). The consequences? Death threats against the band, Beatle record bonfires in the Deep South, universal condemnation by church leaders…essentially putting the kibosh on touring for the Fabs.

Whoops. I think we all owe Yoko an apology.

Thanks to his music journalist cred, he soon gains entree with the Warhol Factory crowd, which leads to his association with The Velvet Underground and a long-time friendship with Lou Reed, Nico, et al. This essentially plants him perennially thereafter at the epicenter of the New York arts scene, where, like a rock ‘n’ roll Forrest Gump, he manages to pal around with everybody who’s anybody from the late 60s ‘til now. He did publicity for The Doors, “discovered” and co-managed The Ramones, did windows, etc.

So why haven’t most people on the planet heard of him? I like to think of myself as a rock ‘n’ roll geek, with an encyclopedic brain full of worthless music trivia…and even I was blissfully unaware of this person until I stumbled across the film on cable the other night. So I am going to have to take all of the gushing interviewees’ word for it that Fields was a “punk pioneer” and essentially the musical taste-maker of the last 5 decades.

Fields proves a raconteur of sorts (the one about a meeting he arranged between Jim Morrison and Nico is amusing) but many anecdotes lead nowhere. For someone allegedly at the vanguard of the music scene for 50 years, he offers little insight. Most of Fields’ reminiscences are variations on “Well, I thought these guys were kinda cute, and I liked their music, so I told so-and-so about them, then I introduced these guys to some other famous guys.” For the most part, it adds up to 104 minutes of glorified name-dropping.

Still, the film is perfectly serviceable as a loose historical chronicle of the NYC music scene during its richest period (via numerous snippets of archival footage), and nostalgic boomers will likely find cameos by the likes of Alice Cooper, Judy Collins, Lenny Kaye, Wayne Kramer, John Sinclair, Jonathan Richman, Iggy Pop, etc. to be enough to hold their interest (although again, more context and/or insight would have sweetened the pot).

The film reminded me of another rock documentary, George Hickenlooper’s The Mayor of Sunset Strip (my review), which profiled L.A. scenester/club manager/DJ Rodney Bingenheimer, who, like Danny Fields, managed to stumble into the midst of every major music sea change from the 1960s onward, rubbing shoulders with any rock ‘n’ roll luminary you’d care to name. Which begs the same question regarding Fields that I posed of Bingenheimer: Is he a true music “impresario”, or merely a lottery-winning super fan?