By Dennis Hartley

(Originally posted on Digby’s Hullabaloo on August 16, 2008)

This week, I’m taking a look at two recent films you may have missed which are now available on DVD. Both fit into a genre I refer to as “Rock ‘n’ Noir”; a twilight confluence of the recording studio and the dark alley.

There is a particularly chilling moment of “art-imitating-life-imitating-art-imitating life” in writer-director Andrew Piddington’s film, The Killing of John Lennon, where the actor portraying the ex-Beatles’ stalker-murderer deadpans in voice-over:

“I don’t believe that one should devote his life to morbid self-attention, I believe that one should become a person like other people.”

Anyone who has seen Scorsese and Shrader’s Taxi Driver will attribute that line to the fictional Travis Bickle, an alienated, psychotic loner and would-be assassin who stalks a political candidate around New York City. Bickle’s ramblings were based on the diary of Arthur Bremer, the real-life nutball who grievously wounded presidential candidate George Wallace in a 1972 assassination attempt.

Although Mark David Chapman’s fellow loon-in-arms John Hinckley would extrapolate further on the Taxi Driver obsession in his attempt on President Reagan’s life in 1981, it’s still an unnerving moment in Piddington’s eerie and compelling portrait of Chapman’s descent into alienation, madness and the murder of a beloved music icon.

Piddington based his screenplay on transcripts of Chapman’s statements and recollections, and focuses on the killer’s complete break with reality, which ultimately culminated in John Lennon’s tragic demise in December of 1980.

The story picks up in the fall of that year, when Chapman (Jonas Ball) was living in Hawaii and reaching the end of his emotional rope. Fed up with a life of chronic underachievement and low self-esteem, he lashes out at his hapless wife (Mie Omori) and domineering mother (Krisha Fairchild).

He is obsessed with J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye; reading the book again and again, until in his own deluded mind, he has transmogrified into the story’s protagonist, Holden Caulfield, on a mission to seek out and denounce all the “phonies” of the world.

He quits his job and takes the first of two fateful solo trips to New York City, where he gleans his “purpose”-to kill his musical idol, John Lennon, for being such a “phony”. His twisted mission is postponed after he attends a screening of Ordinary People, which somehow snaps him back to his senses. Sadly, his creeping derangement did not remain dormant, and we all know what transpired.

Ball is quite convincing in the role; so much so that it will be interesting to see if he can avoid being typecast as a brooding psychopath in future projects (Steve Railsback remains synonymous with Charles Manson to me, several decades after his creepy channeling in Helter Skelter.)

To their credit, director and lead actor do not glorify Chapman or his deeds; nor do they portray him as a boogie man. He’s an everyday Walter Mitty… gone sideways and armed with a .38. The film is a fairly straightforward docu-drama; what makes it compelling is Ball’s edgy unpredictability and the moody, atmospheric cinematography by Roger Eaton.

I can see how boomers like myself, who have the most sentimental attachment to the Beatles, would have an inherent revulsion for reliving this horrible event; I suspect that younger viewers would find the film’s subject matter less morbid and of more objective interest. Clearly, there is an audience for this subject, as there is another film out about Chapman called Chapter 27, starring Jared Leto (I have not seen it; it played the festival circuit last year and is due on DVD September 30).

So what is the point in lolling about in a madman’s head for nearly two hours? And isn’t giving attention to this loser who was a “nobody until I killed the biggest somebody on earth” (the movie’s tag line) only rubbing salt in the wounds of Beatle fans everywhere? Well, perhaps. Then again, it is part of history, part of life. Movies are art, true art reflects life, and life is not always a Disney movie, is it?

I never realized the lengths

I’d have to go

All the darkest corners of a sense

I didn’t know

Just for one moment –

hearing someone call

Looked beyond the day in hand

There’s nothing there at all

-from” Twenty-Four Hours” by Joy Division

1980 was a bizarre yet pivotal year for music. The first surge of punk had come and gone and was being homogenized by the marketing boys into a genre tagged as New Wave. The remnants of disco and funk had finally loosened a tenacious grip on the pop charts, but had not yet fully acquiesced to the burgeoning hip hop/rap scene as the dance music du jour.

What would soon become known as Hair Metal was still in its infancy; and the inevitable merger of “headphone” prog and bloated stadium rock sealed the deal with Pink Floyd’s cynical yet wildly successful 2-LP “fuck you” to the music business, The Wall (the hit single from the album, “Another Brick in the Wall”, was the #2 song on Billboard’s chart for the year, sandwiched between Blondie’s “Call Me” and Olivia Newton-John’s “Magic”). MTV was still a year away from killing the radio stars.

The time was ripe for a new paradigm. For my money, there were several key albums released that year that lurched in that direction. They included Remain in Light by the Talking Heads, Sandinista by the Clash, Black Sea by XTC, Sound Affects by The Jam…and Closer by Joy Division.

Joy Division was a quartet from north of England way who formed in the late 70s. They mixed a punk ethos with a catchy but somber pop sensibility that echoed the stark industrial landscape of their Greater Manchester environs. Along with local contemporaries like The Fall and The Smiths, they seeded what would eventually be dubbed the “Manchester scene” (brilliantly dramatized in Michael Winterbottom’s 2002 film, 24-Hour Party People).

I was blown away the first time I heard Closer; I was struck by the haunted baritone of lead singer Ian Curtis, who had a Jim Morrison-like manner of chanting cryptic lyrics that really got under your skin. Like Morrison, Curtis’ touchstones as a songwriter were more Conrad and Blake than Leiber and Stoller; an invocation of the soul, as opposed to “singing”.

Tragically, by the time that album had been released, and the hit single “Love Will Tear Us Apart” was playing on the radio, Curtis had passed away, at the age of 23. Distraught over his deteriorating marriage and chronic health problems, he committed suicide in May of 1980.

It’s possible that side effects from the myriad anti-seizure medications he was taking for epilepsy had contributed to elevating his depression and despair. The surviving band members regrouped, dusted themselves off and mutated into a more radio-friendly synth-pop outfit called New Order (and the rest, as they say, is history).

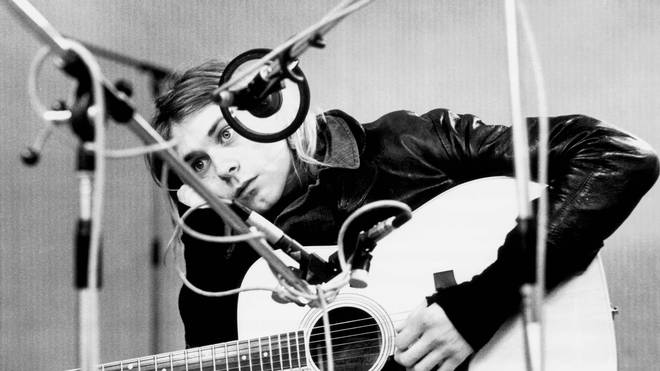

That doesn’t sound like the makings of a feel good summer movie, but I can’t heap enough praise upon Control, first-time director Anton Corbijn’s impressionistic dramatization of Curtis’ short-lived music career. Based on the book Touching from a Distance, a memoir by Curtis’ widow Deborah, the film (shot in stark black and white) eschews the usual biopic formula and instead aspires to setting a certain atmosphere and mood. Corbijn, known previously as a still photographer, actually had a brief professional relationship with Joy Division. He snapped a series of early publicity photos for the band.

The film is fueled by a mesmerizing performance from newcomer Sam Reilly , who a had a bit part in the aforementioned 24-Hour Party People (playing Mark. E. Smith, lead singer of The Fall). He avoids “doing an impression” of Ian Curtis, opting instead for a naturalistic take on a gifted but tortured soul. The fact that Reilly is also a musician certainly doesn’t hurt either (all four actors portraying Joy Division did their own “live” singing and playing).

He holds his own against the seasoned Samantha Morton, who plays his long-suffering wife. Morton is one of the finest and most fearless actresses of her generation; she just keeps getting better. Her character reminded me of the roles that Rita Tushingham tackled head-on in the British “kitchen sink” dramas of the 1960s.

In fact, the intense realism that Reilly and Morton instill into their portrayals of a struggling young working class couple, along with the black and white photography and gritty location filming strongly recalls classics of the aforementioned genre, like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Look Back in Anger and The Leather Boys. Even if you are not a fan of the band, Control is not to be missed.